Stephen Wiesenfeld’s 1975 Supreme Court Triumph: Winning Benefits for Widowers and Advancing Gender Equality

- Denied Social Security survivor benefits after wife’s death in 1972.

- Partnered with Ruth Bader Ginsburg to challenge discriminatory law.

- Unanimous ruling extended parental benefits to fathers nationwide.

In 1975, the United States Supreme Court unanimously struck down a Social Security provision that had excluded widowers from survivor benefits, a decision that immediately affected thousands of families and reshaped perceptions of gender roles in American households.

Stephen Charles Wiesenfeld entered the public eye through profound personal loss, but his journey began years earlier in a life marked by intellectual pursuits and entrepreneurial spirit.

Born on March 12, 1942, in New York City, he grew up in a family that valued education and independence.

He pursued studies in mathematics and computer science, fields that would later define his professional path.

In the late 1960s, he met Paula Polatschek, a dedicated mathematics teacher at Edison High School in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

They married on November 15, 1970, in a ceremony that blended their shared passions for logic and learning.

Paula, originally from Germany, had immigrated to the U.S. and built a stable career, earning significantly more than Stephen—often four times his income from freelance consulting in business systems.

Their partnership reflected the shifting dynamics of the era, where women increasingly entered the workforce as primary earners.

The couple’s life took a tragic turn on June 5, 1972, when Paula went into labor with their first child, Jason.

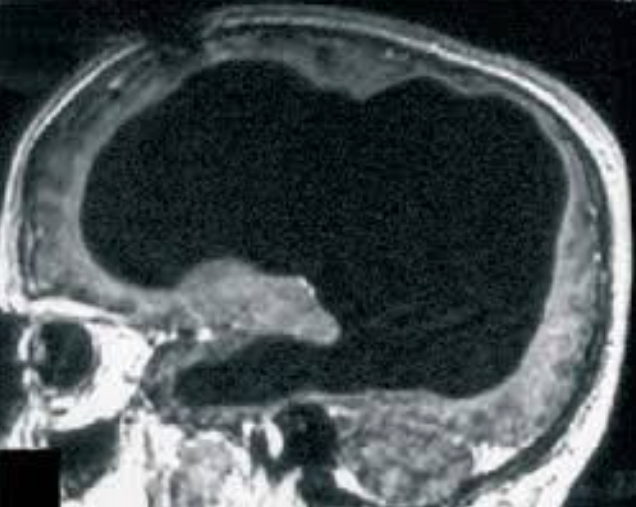

Complications arose swiftly during delivery at Saint Peter’s University Hospital in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

An amniotic fluid embolism, a rare and often fatal condition occurring in about 1 in 40,000 births, claimed her life mere hours after Jason’s arrival.

This medical emergency, which involves amniotic fluid entering the mother’s bloodstream and triggering severe allergic reactions, left Stephen devastated and solely responsible for an infant.

Amniotic fluid embolisms carry a mortality rate of up to 80 percent, underscoring the suddenness of the loss that upended his world.

In the aftermath, Stephen sought stability through the Social Security system, to which Paula had contributed diligently throughout her teaching career.

From 1967 to 1972, she paid into the program via payroll deductions, amassing credits that should have secured survivor benefits for her family.

Stephen applied at the local Social Security office in New Brunswick, intending to use the benefits—potentially up to $248 monthly at the time—to care for Jason full-time while rebuilding his consulting work.

The denial came as a stark rejection: Section 402(g) of the Social Security Act provided “mother’s insurance benefits” exclusively to widows with children under 18, based on the assumption that men were breadwinners and women homemakers.

This gender-based classification, enacted in 1939 amendments, ignored families like the Wiesenfelds, where the wife had been the higher earner.

Outraged by the implication that Paula’s contributions were undervalued, Stephen channeled his grief into action.

He penned a letter to the Home News Tribune in New Jersey, published on March 21, 1973, detailing the injustice and questioning why a woman’s Social Security taxes afforded less protection than a man’s.

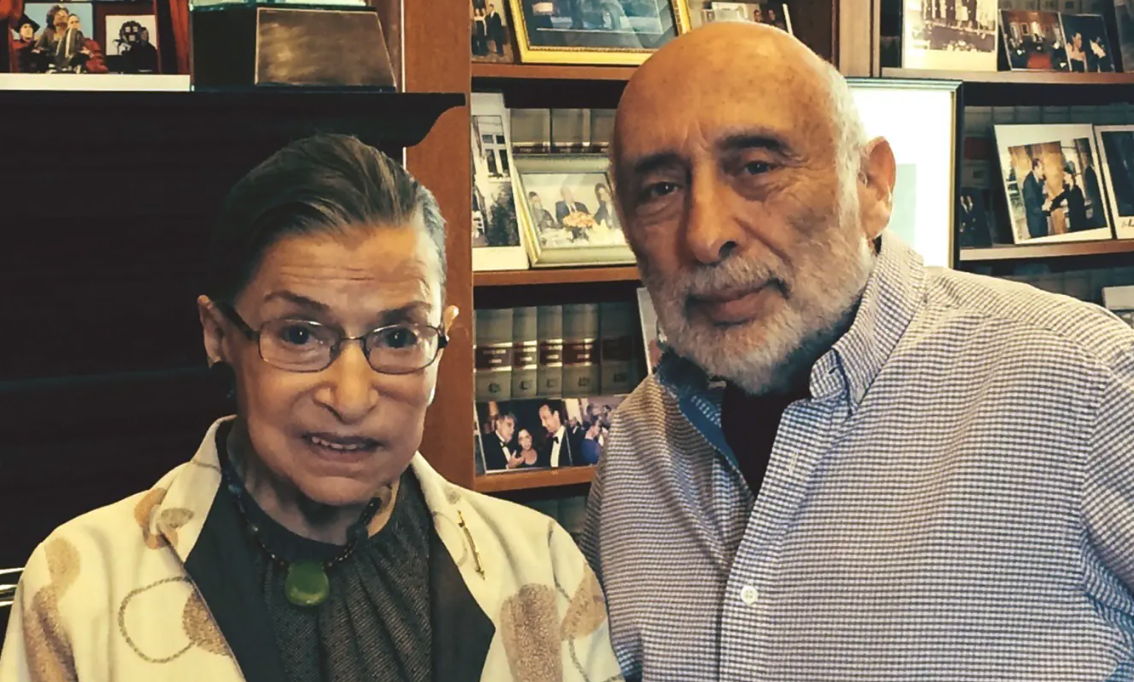

The letter caught the attention of Jane Schenthal, a professor at Rutgers University, who connected him with Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then directing the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project.

Ginsburg, who had cofounded the project in 1972, saw in Stephen’s story a strategic opportunity to dismantle sex-based classifications under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Due Process Clause of the Fifth.

Ginsburg’s approach to gender discrimination cases was deliberate and data-driven.

During the 1970s, she argued six such cases before the Supreme Court, securing victories in five, which collectively invalidated over a dozen statutes rooted in stereotypes.

She incorporated statistics from labor reports showing that by 1970, 40 percent of married women worked outside the home, challenging the notion that families adhered to traditional roles.

In Stephen’s case, she highlighted how the law harmed both sexes: denying men caregiving opportunities and devaluing women’s economic roles.

The lawsuit, filed in 1973 as Wiesenfeld v. Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, progressed through federal courts.

A three-judge panel in the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey ruled in Stephen’s favor in 1974, finding the provision unconstitutional.

The appeal reached the Supreme Court, docketed as Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld (No. 73-1892).

On January 20, 1975, Ginsburg presented oral arguments, emphasizing the statute’s failure to adapt to modern family structures.

She noted that in 1972 alone, over 1.8 million children received survivor benefits, yet widowers like Stephen were systematically excluded.

The justices, including William O. Douglas and Thurgood Marshall, probed the government’s defense, which relied on administrative convenience rather than equity.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. authored the opinion, delivered on March 19, 1975, with an 8-0 vote—Justice William Rehnquist recused himself due to prior involvement in related policy discussions.

The Court held that the gender distinction violated due process, as it provided unequal protection based on archaic assumptions.

The ruling’s immediate effect was transformative. Social Security Administration data from 1975 indicate that the decision opened eligibility to approximately 20,000 widowers initially, with benefits restructured as “child’s insurance benefits” available to any surviving parent.

This shift aligned with broader reforms; by 1983, amendments fully neutralized gender in spousal and survivor provisions, reflecting a 44 percent increase in women’s labor force participation from 1960 to 1980.

For Stephen, the victory proved symbolic. By 1975, he had transitioned to a stable position as a computer systems analyst at RCA Corporation, where his salary surpassed the income cap for benefits—then around $8,400 annually.

He closed his consulting firm to focus on Jason, balancing single parenthood with a demanding career.

Life after the case brought new chapters for Stephen. He relocated to Florida in the 1980s, raising Jason in a supportive community.

Jason pursued higher education, earning degrees in computer science and business, and later started a family of his own.

In 1998, Ginsburg traveled to Florida to co-officiate Jason’s wedding to Amy Cohen, a gesture that underscored their enduring bond.

Stephen’s advocacy extended beyond the courtroom; motivated by Paula’s death, he became a key figure in amniotic fluid embolism awareness.

In 2008, he cofounded the Amniotic Fluid Embolism Foundation, which has since supported over 500 families and funded research grants totaling more than $100,000.

The foundation’s efforts have improved diagnostic protocols, reducing misdiagnosis rates from 50 percent in the 1970s to under 20 percent today.

Ginsburg’s influence on Stephen’s life persisted. She often referred to him as her “favorite plaintiff” in interviews, citing the case as a pinnacle of her strategy to use male plaintiffs to illustrate gender discrimination’s broad harms.

Their friendship deepened over decades; in 2014, at age 72, Stephen remarried to Elaine Wishnow, with Ginsburg officiating the ceremony in the Supreme Court’s East Conference Room—a space reserved for significant judicial events.

This personal milestone highlighted how the case transcended legal boundaries, fostering lifelong connections.

The broader implications of Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld rippled through policy landscapes.

It set precedents for subsequent cases, such as Califano v. Goldfarb in 1977, which equalized spousal benefits, and influenced the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, which provides unpaid leave for caregivers regardless of gender.

By 2010, 28 percent of women retirees were dually entitled to both worker and spousal benefits, up from 5 percent in 1960, reflecting increased economic independence.

Ginsburg’s litigation record—briefing nine major sex-discrimination cases from 1972 to 1980—dismantled barriers, with victories like Frontiero v. Richardson in 1973 elevating scrutiny on gender classifications to intermediate levels.

Stephen’s story also intersected with evolving discussions on parental leave and workplace flexibility.

In the 1970s, only 14 percent of employers offered paternity leave; by 2020, that figure climbed to 27 percent for paid leave, partly due to cultural shifts initiated by such rulings.

His experiences as a caregiving father challenged stereotypes, contributing to a 15 percent rise in stay-at-home dads from 1989 to 2012, according to Census Bureau data.

As he continued speaking engagements into his eighties, including a 2022 lecture at the Blue Ridge Center for Lifelong Learning, Stephen reflected on how one letter sparked national change.

Yet questions linger about the full extent of his influence—how many families today owe their financial security to that pivotal moment, and what hidden biases still linger in modern policies?