Scottsdale Cryonics Facility Housing Ted Williams’ Head Aims to Revive the Frozen Dead

- Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, preserves human remains at -196 degrees Celsius using liquid nitrogen, aiming to enable future revival via advanced medical technologies.

- Baseball legend Ted Williams, cryopreserved in 2002, remains one of the facility’s most famous patients, with his head and body stored separately in stainless-steel dewars amid ongoing debates about the ethics and science of cryonics.

- With costs ranging from $80,000 for neuro-preservation to $220,000 for whole-body cryopreservation, Alcor has attracted over 1,900 living members betting on immortality through suspended animation.

In the heart of Scottsdale’s arid landscape, an unassuming office building conceals a chamber where the boundaries between death and potential rebirth blur.

Here, at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, 222 individuals—referred to not as corpses but as “patients”—lie in a state of profound cryopreservation, their bodies or heads immersed in liquid nitrogen at temperatures plummeting to minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit.

Among them is the severed head of Ted Williams, the Boston Red Sox icon whose .406 batting average in 1941 still stands as a pinnacle of baseball achievement.

Williams, who succumbed to cardiac arrest at age 83, was transported by private jet from Florida to this facility shortly after his passing, igniting a firestorm of family discord and public fascination that continues to echo through discussions of human longevity.

The process begins the moment legal death is declared, when organs remain viable but the heart has ceased.

A standby team, often comprising physicians and technicians, rushes to the scene—anywhere in the world—with a portable ice bath and specialized equipment.

Blood is swiftly replaced with an organ-preserving solution, followed by cryoprotectants designed to prevent ice crystal formation that could shred cellular structures.

At Alcor’s headquarters, the body cools gradually to its final resting state in towering dewars, massive vacuum-insulated tanks that evoke images of science fiction yet operate on principles of physics and chemistry refined over decades.

What if these preserved forms could one day awaken, repaired by nanotechnology capable of mending tissue at the molecular level or biotech innovations that reverse the ravages of disease?

Alcor’s origins trace back to 1972 in California, where visionaries sought to challenge mortality’s finality.

By 1994, seismic risks prompted a relocation to Scottsdale, where the foundation now operates as a nonprofit, sustaining itself through membership dues, donations, and preservation fees.

A recent anonymous $5 million gift from a member underscores the growing investment in research toward reanimation, focusing on fields like regenerative medicine and artificial intelligence to simulate revival scenarios.

Yet, the facility’s most enduring enigma revolves around Williams.

His son, John Henry Williams, and daughter Claudia advocated for cryopreservation, citing a handwritten note from 2000 where the trio pledged to “be put into biostasis after we die” for a chance to reunite in the future.

This pact, scrawled on a napkin during a fishing trip, clashed with claims from Williams’ eldest daughter, Bobby-Jo Ferrell, who insisted her father desired cremation and scattering of ashes over the Florida Keys.

The ensuing legal battle unfolded in courtrooms, revealing intimate family fractures while spotlighting cryonics’ legal ambiguities.

Ferrell’s lawsuit alleged undue influence, but documents upheld the note’s validity, allowing Williams’ remains to stay at Alcor.

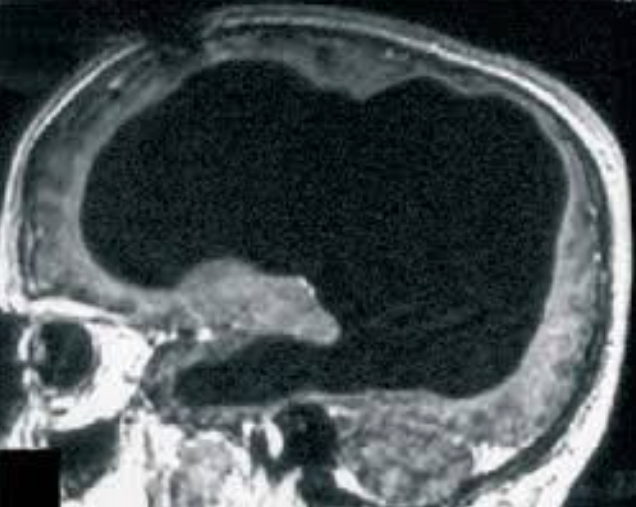

Intriguingly, Williams opted for a hybrid approach: his head underwent neuroseparation—a surgical detachment performed hours postmortem—while his torso was preserved intact, both now suspended in separate containers.

This method, proponents argue, optimizes brain protection, the seat of consciousness, for eventual uploading or repair via emerging neurotechnologies.

But whispers of mishandling have persisted, fueled by a 2009 book from former Alcor executive Larry Johnson, who alleged technicians drilled into Williams’ skull, causing cracks, and even used his frozen head for impromptu batting practice with a tuna can.

Alcor vehemently denies these claims, labeling them fabrications from a disgruntled employee, yet they add a layer of macabre intrigue to the quest for eternal life.

Beyond Williams, Alcor’s dewars hold a diverse array of dreamers.

The first cryopreserved human, psychologist James H. Bedford, frozen in 1967 after battling kidney cancer, shares space with Bitcoin pioneer Hal Finney, who chose preservation in 2014 amid ALS progression.

There’s also two-year-old Matheryn Naovaratpong from Thailand, whose parents, both doctors, turned to cryonics after exhaustive brain surgeries failed to combat her rare cancer.

Emmy-winning TV writer Dick Clair Jones, AI pioneer Marvin Minsky, and Chinese science fiction author Du Hong further illustrate the eclectic appeal, drawing from tech entrepreneurs, scientists, and artists wagering on a post-death renaissance.

Even pets—90 in total, including cats, dogs, and a chinchilla—accompany their owners, with preservation costs scaling from $2,500 for small animals to $30,000 for larger ones, available only to members.

| Key Fact | Details |

|---|---|

| Number of Cryopreserved Patients | 222 human patients, including 116 neuro-only (heads) and the rest whole-body or hybrid |

| Notable Patients | Ted Williams (baseball legend, preserved 2002); James Bedford (first cryopreserved human, 1967); Hal Finney (Bitcoin developer, 2014); Matheryn Naovaratpong (youngest at age 2, 2015) |

| Preservation Costs | $80,000 for neuro-preservation; $220,000 for whole-body; funded often via life insurance policies |

| Facility Details | Located in Scottsdale, Arizona; Moved from California in 1994; Houses patients in liquid nitrogen dewars at -196°C |

| Revival Hopes | Dependent on future advancements in nanotechnology, regenerative medicine, and biotech for cellular repair and reanimation |

Skeptics abound, with bioethicists like Arthur Caplan dismissing cryonics as a “hopeless aspiration” rooted in biological ignorance.

The Society for Cryobiology echoes this, viewing the practice as speculative pseudoscience, unable to reverse the cellular devastation from freezing.

Critics point to the irreversible damage during vitrification—the glass-like solidification process—and question whether revived individuals would recognize a world transformed by centuries of progress.

Alcor counters by emphasizing ethical imperatives: why discard a body when future medicine might cure what killed it?

Their Patient Care Trust, segregated to fund long-term storage, grows at 2% annually, ensuring sustainability without relying on speculative revivals.

Membership swells to 1,927 living individuals, three-quarters male, many from tech hubs like the San Francisco Bay Area, drawn by the allure of transcending natural limits.

Australian clients have joined, and Alcor’s global response teams stand ready, contracting operating rooms as needed.

A 101-year-old woman represents the eldest preserved, her story a testament to cryonics’ broad demographic reach.

Recent advancements, such as improved cryoprotectants reducing toxicity, hint at incremental progress, but the ultimate breakthrough—reviving a cryopreserved mammal—remains elusive.

Could nanotechnology robots swarm through veins, stitching neurons back together? Might biotech breakthroughs in organ printing extend to full-body restoration?

WATCH: Inside the US lab freezing the dead at -196C

As Alcor refills liquid nitrogen weekly, monitoring via computer sensors, the facility hums with quiet anticipation.

Williams’ head, once mistreated according to unverified accounts that included hazardous chemical dumps and eerie disposal jokes, now symbolizes both hope and hubris.

In 2017, marking 50 years since Bedford’s preservation, experts pondered if cryonics could evolve from fringe to mainstream.

Today, with gene editing and stem cell therapies advancing, the line thins further.

What undisclosed innovations might Alcor be pursuing in their labs, perhaps accelerating the day when a thawed patient draws breath again?

And if that moment arrives, will Ted Williams, the Splendid Splinter, step into a batter’s box in a world where death is optional, or will the frozen dead reveal secrets that redefine humanity itself?