Man Found to Be Missing 90% of His Brain but Still Living a Normal Life

In a stunning case that has baffled scientists and opened new doors to understanding the complexity of the human brain, a French man who has lost 90% of his brain tissue continues to live a seemingly normal life.

The findings, first published in The Lancet back in 2007, have resurfaced recently, prompting fresh scientific debate about consciousness, brain plasticity, and the limits of human resilience.

This case, which seems almost too strange to be true, has raised a fundamental question: if the brain can lose so much of its mass and still function almost like a regular brain, what does that tell us about the true nature of consciousness?

The Startling Discovery

At first glance, this case appears to be a story of extreme medical mystery.

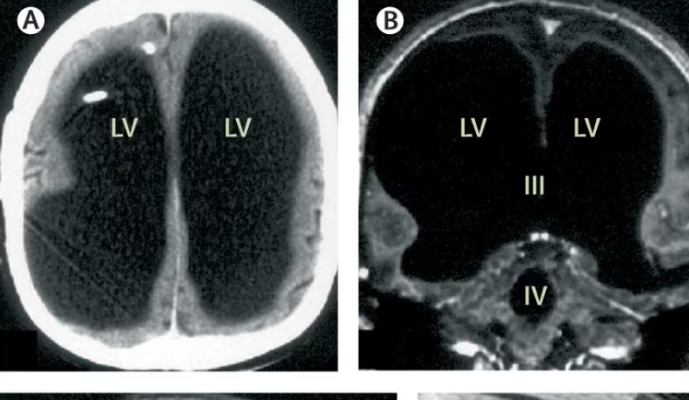

The man, whose identity has been kept private, was 44 years old when he was first diagnosed with hydrocephalus, a condition characterized by the abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain.

Over the course of 30 years, this fluid buildup gradually destroyed much of his brain tissue.

What’s even more remarkable is that the man only discovered the extent of his condition after seeking medical attention for a mild weakness in his left leg.

Imagine going about your daily life, completely unaware that your brain is slowly being eaten away by fluid.

It’s almost surreal to think that this man lived for decades without realizing that his brain matter was progressively being replaced by liquid.

For anyone, this would sound like the plot of a science fiction novel. But for this man, it was reality.

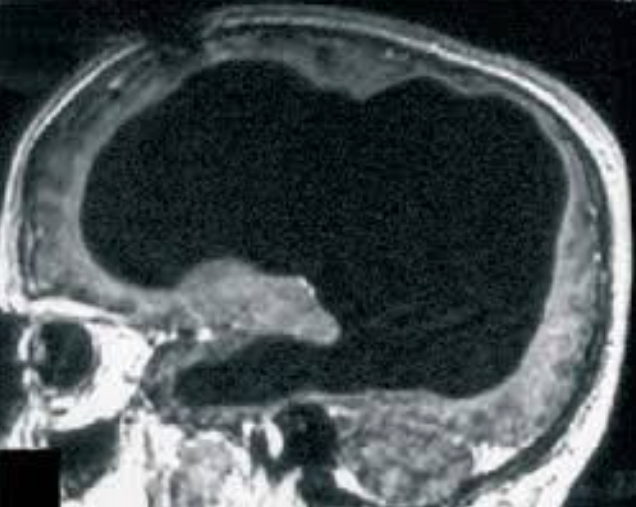

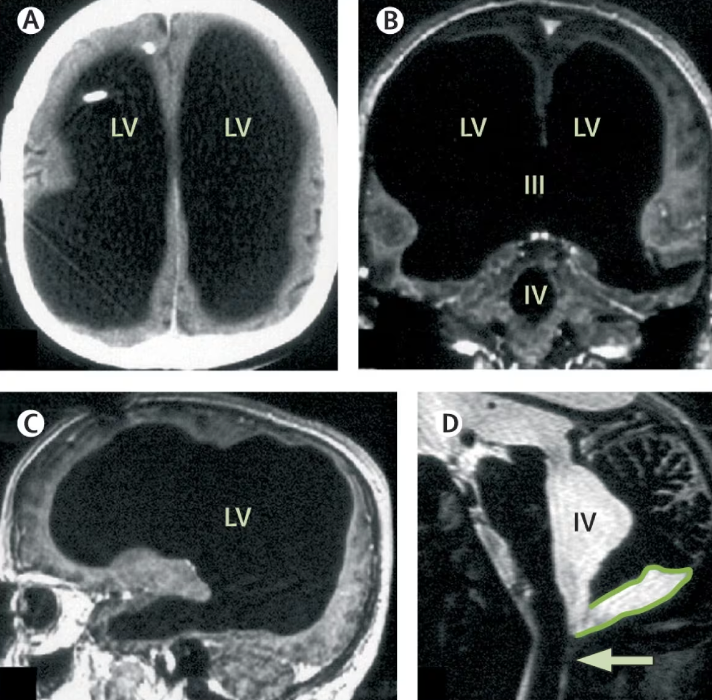

It wasn’t until imaging studies—such as MRIs—were conducted that the extent of the damage was revealed.

The skull, which should have contained a significant amount of brain tissue, was found to be almost entirely filled with cerebrospinal fluid, leaving behind only a minimal layer of actual brain matter.

His condition was so severe that what remained of his brain was reduced to a thin layer along the edges of his skull.

Yet, despite losing most of his brain, the man was able to function in a way that seemed almost identical to someone with a fully intact brain.

He was able to perform daily tasks, interact socially, and even hold a steady job.

He lived life without the major impairments typically associated with such severe brain damage.

The obvious question, of course, is how? How could a person live a normal life with so little brain tissue?

The Unfathomable Mystery of Consciousness

This question has left scientists scratching their heads for years.

The traditional understanding of consciousness has long been that it is tied to specific regions of the brain.

For instance, scientists have historically believed that areas like the claustrum—a small, thin sheet of neurons deep in the brain—and the visual cortex are essential for the experience of consciousness.

These regions have been thought to play a critical role in the brain’s ability to process and become aware of sensory input, emotions, and cognitive functions.

But here’s where things get even more complicated. The man in this case was missing nearly all the brain tissue that would normally be required for such functions.

And yet, he was still conscious, aware of his surroundings, and able to interact with the world as most of us do.

This discovery has forced scientists to reconsider their assumptions about what consciousness truly is and where it resides.

One researcher at the forefront of this shift in thinking is Axel Cleeremans, a cognitive psychologist at Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Cleeremans has introduced the idea of the “radical plasticity thesis,” which proposes that consciousness is not a fixed attribute tied to specific regions of the brain, but rather an emergent property.

According to this theory, consciousness is something that evolves and adapts depending on the condition of the brain.

In simpler terms, Cleeremans suggests that the brain isn’t necessarily dependent on particular regions to maintain consciousness.

Instead, the brain as a whole can adapt to loss or damage by reconfiguring itself in ways we don’t fully understand yet.

This ability for the brain to “learn” and “re-describe” its own activity through experience means that consciousness can persist, even in the face of severe brain damage.

To illustrate this idea, Cleeremans uses the example of the brain’s ability to compensate for deficits.

If one area of the brain is damaged, other parts can often take over its functions.

For instance, if someone loses their sight, other sensory pathways, like those for touch, may become heightened, as seen in some blind individuals.

In the case of the man with hydrocephalus, it’s possible that his brain adapted to its drastically altered state by rerouting its functions in ways that allowed him to maintain consciousness and cognitive abilities.

Rethinking Brain Function and Resilience

The implications of this case are profound. It challenges some of the most fundamental assumptions about how the brain works and what it means to be “conscious.”

If consciousness isn’t strictly tied to specific brain regions, then what exactly does it depend on?

Could it be that consciousness is more fluid and adaptable than we’ve ever realized?

And if so, how does this change our understanding of brain injuries, aging, and neurological diseases?

This discovery also raises questions about the resilience of the human brain.

How much can the brain really adapt and compensate before it reaches its limits?

The man in this case, despite his severe brain damage, lived a functional life, but what about other individuals with brain injuries or neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s?

Could they too benefit from some form of neural plasticity that allows them to regain abilities or maintain function in the face of damage?

For scientists, the case of the 44-year-old French man underscores the mystery of brain function, revealing just how little we understand about the full potential of neural adaptation.

Researchers are now more eager than ever to explore the mechanisms that allow the brain to maintain consciousness even with significant damage.

Could this case offer new hope for individuals with traumatic brain injuries or degenerative diseases? Could it change the way we treat brain-related illnesses?

Watch: Man has Just a Seven-Second Memory: Shocking Virus Infection!

The Power of Brain Plasticity: Hope for the Future?

The findings from this case have sparked fresh interest in the concept of brain plasticity—the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize and adapt itself.

The more researchers delve into the idea that consciousness isn’t anchored in specific areas of the brain, the more they realize that the human mind is capable of far more than previously imagined.

In some ways, this case brings to light a hopeful possibility for those suffering from brain-related conditions.

Could treatments designed to promote brain plasticity help to reverse some of the effects of brain damage or slow the progression of degenerative diseases?

While this idea is still in its early stages, it offers a glimmer of hope for patients who may have been written off as “irreparable” or “beyond help.”

Of course, it’s important to remember that this case is an outlier.

The man’s situation is extremely rare, and his experience cannot be generalized to all cases of brain damage or neurological conditions.

But it does challenge us to rethink the boundaries of what’s possible in brain science and offers new possibilities for how we might treat the brain in the future.

As scientists continue to explore this mind-boggling case, they’re forced to confront the limits of their understanding and accept that there’s much more to learn about the mysterious ways in which the human brain functions.

Could the brain be far more resilient and adaptable than we ever thought? This extraordinary case suggests that the answer might be yes.

The research is far from over, and perhaps in the future, we will look back at this case as the key to unlocking even greater mysteries of the human mind.

Watch: Boy Missing 80% of Brain Beats the Odds

Jaxon Emmett Buell (August 27, 2014 – April 1, 2020) was an American child born with approximately 80% of his brain missing due to anencephaly.

Defying doctors’ predictions that he would not survive past his first birthday, Jaxon lived for more than five-and-a-half years.