Gerda Weissmann Klein: Holocaust Survivor of 350-Mile Death March Who Married Her Liberator in 1946

- Endured six years in Nazi labor camps starting at age 15.

- Authored bestselling memoir ‘All But My Life’ adapted into Oscar-winning film.

- Founded Citizenship Counts, educating 1 million+ on civic responsibility.

In a staggering testament to resilience, Gerda Weissmann Klein survived a grueling 350-mile death march through a brutal European winter, one of only 120 women out of 2,000 who began the trek, emerging to rebuild a life that influenced millions through her advocacy and writings.

Gerda Weissmann entered the world on May 8, 1924, in the industrial town of Bielsko, Poland, a community renowned for its thriving textile mills that employed thousands in the interwar period.

Born to Julius Weissmann, a successful fur trader whose business supported a comfortable middle-class existence, and Helene Mueckenbrunn Weissmann, a homemaker who managed their household with quiet efficiency, Gerda grew up alongside her older brother Arthur in a close-knit Jewish family.

The Weissmanns resided in a spacious apartment where Gerda enjoyed a childhood filled with simple pleasures: skiing in the nearby Beskid Mountains during winters, tending a small garden, and attending Polish public schools where she excelled in literature and languages.

By the 1930s, Bielsko’s Jewish population numbered around 8,000, representing about 20 percent of the town’s residents, fostering a vibrant cultural scene that included synagogues, Yiddish theaters, and community organizations.

Yet beneath this stability loomed the rising shadow of antisemitism across Europe, with Poland’s Jewish community facing increasing restrictions under nationalist policies that affected over 3 million individuals nationwide.

The invasion shattered this world on September 3, 1939, when German forces swept into Bielsko just days after the start of World War II, part of a blitzkrieg that conquered Poland in under a month and led to the occupation of territories home to 1.7 million Jews.

At 15, Gerda witnessed her hometown transform into a site of terror: curfews imposed, radios confiscated, and Jewish businesses marked for boycott.

Her father suffered a heart attack amid the chaos, weakening the family further.

In October 1941, Arthur, then 19 and studying engineering, received a deportation order to a labor camp; he vanished into the Nazi machinery, one of the 1.5 million Polish Jews deported during the early war years.

Gerda and her parents clung to hope, but by June 1942, authorities forced them into Bielsko’s ghetto, a cramped district where over 4,000 Jews endured starvation rations of less than 1,000 calories daily and constant threats of violence.

Life in the ghetto proved a prelude to greater horrors.

In August 1942, the Nazis liquidated the area, separating families in selections that sent 90 percent of Bielsko’s Jews to Auschwitz, just 30 miles away, where gas chambers claimed over 1.1 million lives throughout the war.

Gerda’s parents boarded trains bound for extermination, while she, deemed fit for work at 18, entered the slave labor system.

Transported to Sosnowiec transit camp, she underwent brutal medical inspections before assignment to Bolkenhain, a subcamp of Gross-Rosen where women wove textiles for the German military under grueling conditions: 12-hour shifts, minimal food amounting to 600 calories per day, and frequent beatings that left permanent scars.

Over the next three years, Gerda shuttled between camps—Merzdorf, Landshut, Grünberg—enduring typhus outbreaks that killed thousands and lice infestations that spread disease rapidly.

In one facility, she operated looms producing uniforms for the Wehrmacht, contributing to a forced labor network that exploited 7.5 million civilians across Europe.

As Allied forces closed in during late 1944, the Nazis intensified evacuations.

On January 29, 1945, Gerda joined approximately 4,000 women from Grünberg on a death march, though initial estimates suggest the group she marched with numbered around 2,000 after splits.

The journey spanned over 350 miles through snow-covered Silesia, with temperatures plummeting to -20 degrees Fahrenheit, claiming lives at a rate of dozens per day from exposure, shootings, and exhaustion.

Guards provided no shelter, forcing marches of 20 miles daily on roads lined with frozen corpses.

Gerda wrapped her feet in rags after her shoes disintegrated, and her hair turned prematurely white from malnutrition, a condition affecting many survivors due to severe vitamin deficiencies.

By April, the group dwindled to under 150, herded into an abandoned bicycle factory in Volary, Czechoslovakia, where SS officers rigged explosives before fleeing as Soviet and American troops advanced.

Liberation arrived on May 7, 1945, one day shy of Gerda’s 21st birthday.

A rainstorm thwarted the bomb, and U.S. Army scouts from the 5th Infantry Division pried open the doors, announcing the war’s end in Europe—a conflict that had claimed 6 million Jewish lives.

Weighing just 68 pounds, Gerda staggered outside to confront a Jeep bearing a white star, symbol of the Allies who liberated over 250,000 camp survivors in the war’s final months.

Lieutenant Kurt Klein, a 25-year-old intelligence officer born in Walldorf, Germany, in 1920, approached her.

Kurt had fled Nazi Germany in 1937 at 17, after his family faced escalating persecution following the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stripped Jews of citizenship and affected 500,000 individuals.

Settling in Buffalo, New York, he worked menial jobs while his siblings emigrated, but efforts to secure visas for his parents failed; they perished in Auschwitz in 1942, among the camp’s 1.1 million victims.

Kurt’s question—”Are you Jewish?”—and his gesture of holding the door open for Gerda marked a profound restoration of dignity after six years of dehumanization.

Inside the factory, amid dying women on straw pallets, Gerda recited Goethe’s “Edel sei der Mensch, hilfreich und gut,” astonishing Kurt with her preserved intellect despite the horrors.

Hospitalized in Volary’s makeshift facility, Gerda battled life-threatening complications: frostbite requiring skin grafts, organ damage from starvation that reduced her life expectancy projections, and psychological trauma shared by 80 percent of survivors.

Kurt visited daily, bringing chocolate and fruit—rarities after years of ersatz bread—and sharing stories of his American acculturation, including his 1942 enlistment in the U.S. Army where he interrogated prisoners and mapped enemy positions across France and Germany.

Their bond deepened over months. Kurt, who had interrogated high-ranking Nazis and witnessed Buchenwald’s liberation in April 1945, found in Gerda a kindred spirit who understood loss intimately.

By summer, as Gerda regained 30 pounds through careful nutrition plans overseen by Army doctors, they discussed rebuilding lives amid the displacement of 11 million Europeans.

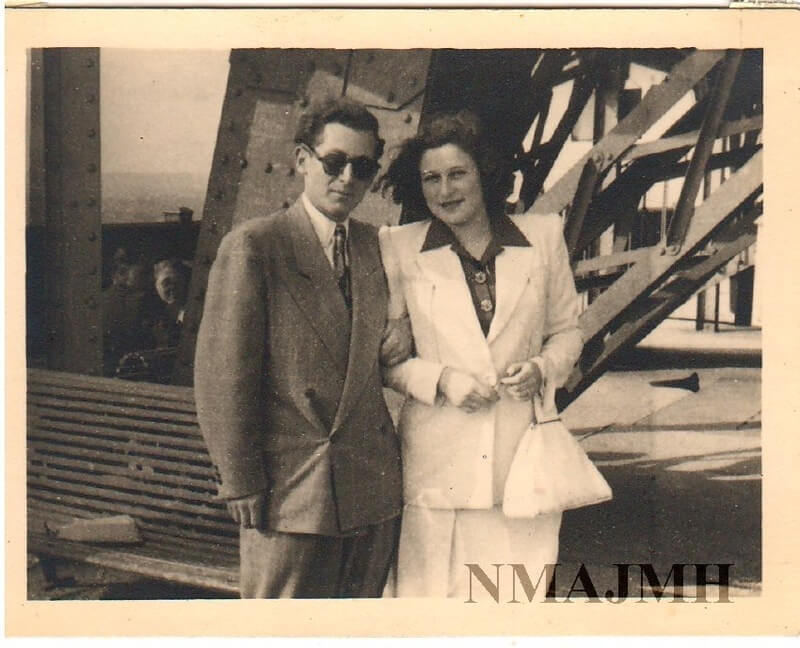

Kurt proposed in September 1945, and after his demobilization, they wed on June 18, 1946, in Paris’s Rothschild Synagogue, attended by 50 guests including fellow survivors.

Gerda’s silk parachute wedding dress, fashioned from Army materials, symbolized renewal; they lit candles for lost family members, a ritual echoing Yizkor traditions observed by millions postwar.

Emigrating to the United States in September 1946 aboard a converted troopship, they settled in Buffalo, where Kurt launched a printing company that grew to employ 50 workers by the 1960s, specializing in commercial labels.

Gerda naturalized as a citizen in 1951, embracing civic duties that later inspired her work.

They raised three children: Vivian (born 1949), Leslie (1951), and James (1953), in a suburban home where Gerda instilled values of empathy, hosting annual Seder meals for up to 40 guests.

Motherhood brought challenges; Gerda underwent multiple surgeries for war-related health issues, including a hysterectomy in her 30s due to uterine damage from malnutrition.

Gerda’s voice emerged publicly with her 1957 memoir, All But My Life, which detailed her experiences in 224 pages and sold over 1 million copies worldwide, translated into eight languages.

The book, praised by The New York Times for its unflinching honesty, became required reading in over 500 U.S. schools by the 1980s.

In collaboration with Kurt, she co-authored The Hours After in 2000, a collection of their letters spanning 50 years, revealing intimate reflections on healing.

Other works included Promise of a New Spring (1981), a children’s book on Holocaust themes, and A Boring Evening at Home (2004), essays on family life.

Her 1995 HBO documentary, One Survivor Remembers, narrated her story with archival footage and won an Academy Award for Best Documentary Short, reaching audiences of 20 million through broadcasts and educational screenings.

Beyond writing, Gerda and Kurt dedicated decades to Holocaust education, speaking at over 1,000 events annually by the 1990s, addressing audiences totaling 2 million, including military academies and corporations.

After the 1999 Columbine High School shooting that killed 13, they visited Colorado multiple times, counseling students on resilience, drawing parallels to postwar recovery where 300,000 displaced Jews rebuilt communities.

In 2008, at 84, Gerda founded Citizenship Counts, a nonprofit that developed curricula on naturalization, impacting over 1 million students in 40 states through interactive programs emphasizing civic engagement.

The organization partnered with schools and scouts, hosting ceremonies where immigrants shared stories, fostering tolerance in an era when hate crimes against Jews rose 37 percent from 2016 to 2017.

Kurt’s death on February 19, 2002, from colon cancer at 81 left Gerda to carry their mission alone, relocating to Scottsdale, Arizona, for its milder climate beneficial for her lingering health concerns.

She continued lecturing, appearing on Oprah in 1996 to an audience of 20 million and at the United Nations in 2005 for the 60th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation, attended by world leaders.

President Barack Obama presented her the Presidential Medal of Freedom on February 15, 2011, America’s highest civilian honor, awarded to only 16 recipients that year, citing her as an exemplar of human spirit amid recipients like Maya Angelou.

Gerda’s family expanded to eight grandchildren and, by her passing, 27 great-grandchildren, many involved in philanthropy; granddaughter Alysa Ullman leads Citizenship Counts, extending programs to virtual formats during the COVID-19 pandemic that reached 500,000 online participants.

In 2018, she keynoted at the March of the Living in Poland, walking Auschwitz grounds with 12,000 youth, symbolizing transmission of memory as survivor numbers dwindle below 200,000 globally.

Her archives, donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2019, include 500 letters and artifacts viewed by 400,000 annual visitors, preserving voices for future research.

Gerda Weissmann Klein departed on April 3, 2022, at 97 in Scottsdale, her legacy etched in tributes from figures like Hillary Clinton, who noted her impact on women’s rights advocacy.

Yet as digitized letters reveal untold correspondences with global leaders, one wonders what further insights into her unyielding optimism await discovery, and how her story might inspire emerging generations facing their own trials of division and despair.