438 Days Lost at Sea: ‘I Ate My Fingernails to Survive’ (Real-Life Cast Away Story)

Ebon Atoll, Marshall Islands – January 2014

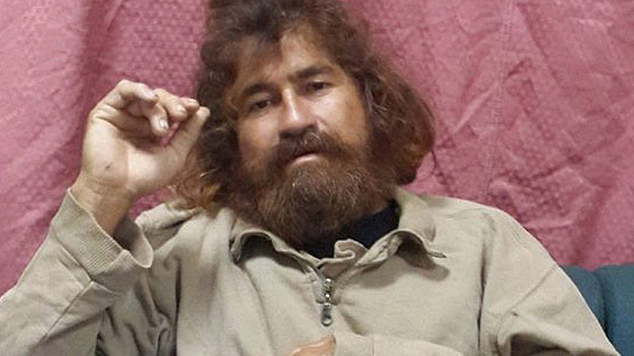

The two policemen squinted at the disheveled man slumped in their boat. His beard was a bird’s nest, his skin leathery from months under the Pacific sun, and his body so emaciated he could barely stand.

Salvador Alvarenga, a 36-year-old fisherman from El Salvador, had just washed ashore on Tile Islet—a dot of land 6,700 miles from where he’d vanished 14 months earlier.

Locals Emi Libokmeto and her husband Russel Laikidrik found him crawling naked through the sand, muttering in Spanish. “He looked like he’d been through hell,” Emi recalled.

This wasn’t a Hollywood survival flick. It was a real-life saga of desperation, ingenuity, and a will to live that defied all odds.

The Ill-Fated Fishing Trip

On November 17, 2012, Alvarenga set off from Costa Azul, Mexico, in a 25-foot fiberglass boat nicknamed Titanic.

A veteran fisherman, he’d planned a routine two-day trip with his usual crewmate, Ray Perez.

But when Perez bailed last minute, Alvarenga recruited Ezequiel “Piñata” Córdoba, a 22-year-old soccer player with zero fishing experience.

The duo stocked the boat with 70 gallons of gasoline, 16 gallons of water, 50 pounds of sardines for bait, a half-charged radio, and a GPS that “wasn’t waterproof.”

They motored 50 miles offshore, catching sharks, tuna, and mahimahi.

By day two, their icebox held 1,100 pounds of fish—enough to earn $400, a small fortune in their coastal village. Then the storm hit.

Trapped in the Storm’s Fury

Waves as tall as two-story buildings pummeled the boat. Seawater flooded the deck.

Alvarenga, gripping the tiller, screamed into the radio: “Willy! The motor is ruined! We’re getting fucked out here!” His boss, Willy, promised a rescue, but the radio died.

Then the GPS shorted out. With no anchor, the men tossed their catch overboard to lighten the load. “We were throwing away $400, but we had no choice,” Alvarenga later said.

For 48 hours, they bailed water nonstop. Córdoba, vomiting and sobbing, clung to the rails.

Alvarenga smashed the dead engine with a fish club in frustration. By nightfall, hypothermia set in.

The pair crammed into an overturned icebox, hugging each other for warmth. “We were like two wet cats,” Alvarenga recalled.

Survival Mode: Turtles, Urine, and Hallucinations

Adrift and lost, the men faced a grim new routine. Alvarenga taught himself to catch fish bare-handed, kneeling at the boat’s edge and snatching them mid-swim.

They ate raw tuna, seabirds, and turtles—slicing their throats to drink blood. When dehydration struck, they sipped urine and rainwater.

“It tasted salty, but we laughed like kids when it rained,” Alvarenga said.

But Córdoba cracked. After weeks of raw meat, he refused to eat. “I’m dying,” he whispered.

Alvarenga begged him to stay alive, even promising to visit his mother in Mexico. On day 60, Córdoba succumbed.

“I propped up his body so he wouldn’t wash away,” Alvarenga said. “I talked to him for days like he was still here.”

Alone, Alvarenga’s mind unraveled. He hallucinated feasts of grilled meat and imaginary lovers.

“I tasted the best meals of my life,” he admitted. To track time, he counted 15 full moons, just as his grandfather had taught him.

Watch: Insane way man survived 438 days lost at sea (Infographics video)

The Miraculous Landing

By January 2014, Alvarenga spotted shorebirds—a sign of land. Drifting toward Tile Islet, he dove into the surf and let a wave toss him ashore.

Russel and Emi found him hours later. “He kept drawing a boat and a man in the sand,” Emi said.

“We didn’t speak Spanish, but we knew he’d been through something terrible.”

News of the “real-life Cast Away” spread fast. Reporters from The Guardian and Agence France-Presse scrambled to Ebon Atoll, while skeptics dismissed his story as a hoax.

“No one survives 14 months at sea,” critics argued online.

The Proof in the Details

But evidence piled up. The boat’s registration matched Mexican records.

US Embassy officials noted Alvarenga’s parasite-riddled liver and scars from turtle bites.

Oceanographers mapped his drift, aligning with Pacific currents. “His story checks out,” said adventurer Jason Lewis, who crossed the Pacific by pedal boat. “It’s brutal, but plausible.”

Mexican search teams confirmed they’d scoured the coast for Alvarenga in 2012 but called off efforts after two days due to storms.

“The winds were too strong,” said rescue official Jaime Marroquín.

Life After the Drift

Rescue didn’t end the nightmare. Alvarenga slept with lights on, terrified of darkness. He panicked near water, even puddles.

“I’d wake up screaming, thinking I was back at sea,” he said. Doctors diagnosed anemia and liver damage from years of raw meals.

In 2015, he visited Córdoba’s mother in Chiapas, Mexico. “I told her he died peacefully,” Alvarenga said. “She cried, but thanked me for coming.”

His newfound fame brought chaos. A lawsuit erupted when his ex-lawyer demanded $1 million for “breach of contract” over media deals.

Alvarenga shrugged it off. “Money doesn’t matter when you’ve stared death in the face,” he said.

A Legacy of Resilience

Today, Alvarenga lives quietly in El Salvador, still haunted by memories of circling sharks and endless horizons.

“I survived by imagining my family’s voices,” he said. “My mother’s prayers kept me alive.”

His advice? “Never give up. You only get one life—appreciate it.”

For the rest of us, his story is a visceral reminder: the ocean is a merciless judge. But sometimes, just sometimes, it spares a soul brave enough to fight.