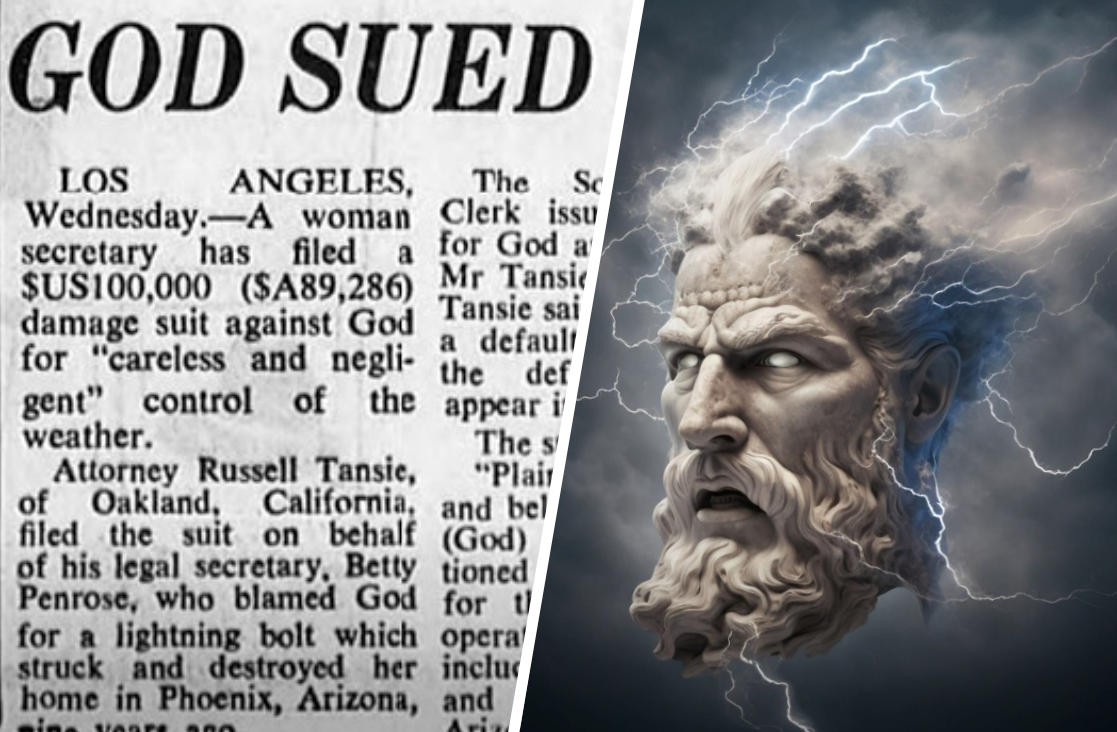

Betty Penrose: The woman who tried to sue God after lightning struck her home

- Betty Penrose’s Phoenix residence burned down from a lightning strike on August 17, 1960.

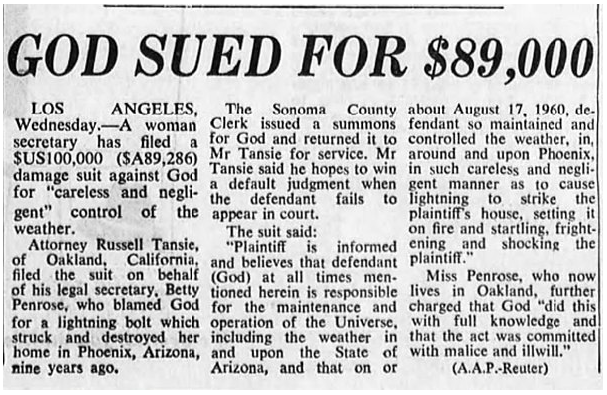

- Her attorney filed a negligence lawsuit against God in May 1969, seeking $100,000 in damages.

- The court awarded a default judgment when the defendant failed to appear.

Each year, lightning strikes claim around 20 lives in the United States and cause property losses exceeding $1 billion, but few victims pursue justice beyond insurance claims.

Betty Penrose, however, took her grievance to an unprecedented level by naming God as the defendant in a civil suit, challenging the boundaries of law and theology in a case that captivated the nation.

The saga began on a stormy summer day in Phoenix, Arizona. Penrose, a legal secretary in her thirties, returned home to find her property engulfed in flames after a powerful bolt hit the structure.

Firefighters battled the blaze for hours, but the damage proved total, with estimates placing the loss at over $75,000 in 1960 dollars – equivalent to roughly $800,000 today when adjusted for inflation.

Neighbors described the scene as chaotic, with thunder echoing through the valley and emergency vehicles lining the street.

Penrose escaped unharmed, yet the event left her without shelter and grappling with the randomness of natural forces.

In the aftermath, Penrose turned to her employer, Russell T. Tansie, a local attorney known for his unconventional approaches to litigation.

Tansie, practicing in Maricopa County, saw an opportunity in the misfortune. Insurance policies often classify lightning as an “act of God,” a term that exempts companies from certain liabilities.

Tansie flipped this phrase on its head, arguing that if such events fell under divine purview, then God bore responsibility for the negligence involved.

This logic formed the backbone of the complaint filed in Superior Court on May 13, 1969.

The lawsuit detailed God’s alleged failure to exercise due care over weather patterns, permitting the strike despite omnipotent control.

Tansie demanded compensation for property destruction, emotional distress, and related costs, totaling $100,000.

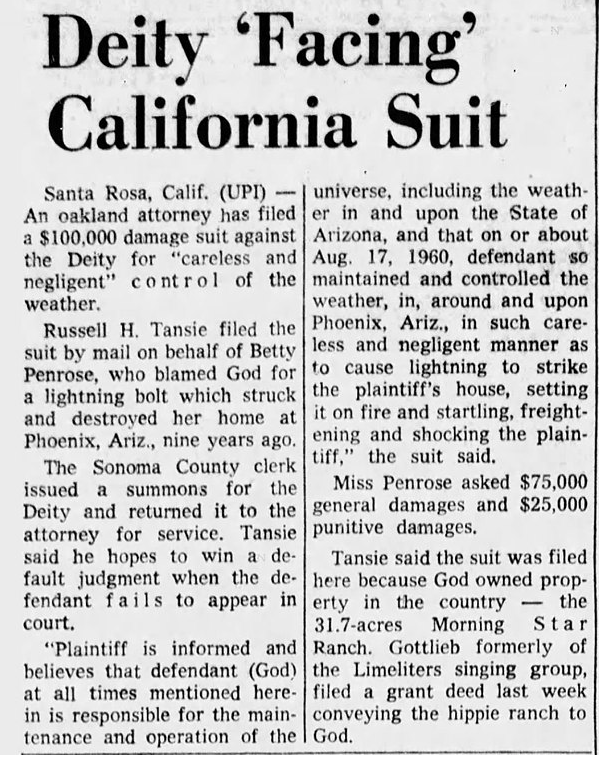

To establish jurisdiction, he linked the case to a recent development in California.

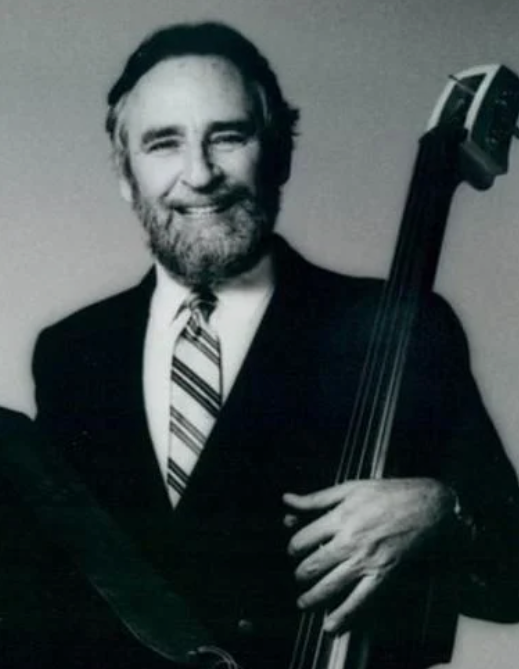

Musician Lou Gottlieb had deeded his 31-acre Morning Star Ranch in Sonoma County to God in an attempt to evade zoning violations tied to his hippie commune.

Tansie contended that this ownership made God a resident of the state, amenable to service of process.

Court records show the summons was served at the ranch, with Tansie asserting that God’s universal presence negated traditional delivery challenges.

Legal scholars at the time debated the validity, noting that fewer than 5% of unusual negligence suits ever reach trial due to procedural hurdles.

Yet Tansie pressed forward, drawing media attention from outlets across the country.

Reporters flocked to Phoenix, interviewing Penrose about her motivations. She expressed frustration over the “act of God” clause, which had complicated her insurance payout, leaving her with mounting bills.

As the case progressed, questions arose about representation for the defendant.

One San Quentin inmate, Paul Yerkes Bechtel, claimed to be God incarnate and offered to appear, but his bid went unheeded.

From Kenya, Joseph Njue volunteered to defend the Almighty, citing biblical precedents, though the court dismissed such interventions as extraneous.

The hearing date approached without any response from the named party, heightening public intrigue. Would the divine intervene in mortal affairs?

On the day of the proceedings, the courtroom filled with spectators, including theologians and curiosity seekers.

When God did not materialize, Judge Samuel P. King granted a default judgment in Penrose’s favor, a rare outcome in civil litigation where defaults occur in about 10% of cases nationwide.

The ruling awarded the full $100,000, plus court costs, marking a symbolic victory.

Enforcement, however, posed an insurmountable barrier – how does one collect from an ethereal entity?

Tansie quipped that divine assets, like the universe itself, could theoretically satisfy the debt, but no garnishment followed.

This outcome sparked broader discussions on the intersection of faith and jurisprudence.

In the United States, courts handle over 100 million cases annually, yet those involving supernatural defendants remain anomalies, comprising less than 0.001% of filings.

Penrose’s action highlighted vulnerabilities in legal language, prompting some insurers to revisit policy wording.

Statistics from the National Weather Service reveal that lightning strikes the ground approximately 25 million times each year in the U.S., with Florida experiencing the highest incidence at over 1.4 million annual bolts.

Such data underscores the tangible risks Penrose faced, far from mere abstraction.

To illustrate the scale of lightning’s impact, consider the following key figures:

| Category | Annual U.S. Average (2015-2024) | Notable Details |

|---|---|---|

| Fatalities | 20 | Males account for 80% of victims |

| Injuries | 200-300 | Often result in neurological issues |

| Property Claims | 73,000 | Homeowners file most frequently |

| Insured Losses | $1.2 billion | Includes fires and electrical surges |

| Strikes per Square Mile | 4-6 in high-risk areas | Peaks in summer months |

These numbers, drawn from insurance industry reports, emphasize why Penrose’s story resonated – it personalized a widespread hazard.

Beyond Arizona, similar bolts cause wildfires that scorch millions of acres yearly, with economic ripple effects reaching $10 billion in extreme seasons.

Penrose’s case did not stand alone in the annals of eccentric litigation.

In 1971, Pennsylvania inmate Gerald Mayo sued Satan for civil rights violations, alleging the devil placed obstacles in his path.

The court declined, citing service issues. Decades later, in 2007, Nebraska Senator Ernie Chambers filed against God to protest barriers to justice, seeking an injunction against natural disasters.

His suit, dismissed for lack of address, aimed to spotlight systemic flaws rather than collect damages.

Internationally, Romanian prisoner Pavel Mircea targeted the Orthodox Church as God’s proxy in 2005, claiming breach of baptismal contract after committing murders.

The case dragged until 2007, when judges ruled God immune from earthly jurisdiction.

Even in India, attorney Chandan Kumar Singh challenged Lord Rama in 2016 over mythological mistreatment of his wife Sita, but the high court deemed it impractical.

These precedents, spanning continents, reveal a pattern: humans grappling with misfortune through legal channels when conventional explanations fall short.

Tansie’s strategy, tying the suit to tangible property like Morning Star Ranch, set Penrose’s apart, though a California judge later invalidated Gottlieb’s deed, declaring God neither a natural nor artificial person capable of holding title.

This ruling cast doubt on the judgment’s longevity, yet it endured in public memory as a win.

Debates ensued among legal experts, with some arguing it exposed absurdities in tort law, where negligence claims require duty, breach, and harm – elements stretched thin against omnipotence.

Others viewed it as a commentary on accountability, questioning why divine acts escape scrutiny while human errors invite lawsuits.

Penrose herself faded from headlines, but her boldness inspired cultural references, from books on quirky cases to films exploring faith’s limits.

As lightning continues to strike – with over 40,000 thunderstorms daily worldwide generating 8 million bolts – one wonders if another bold plaintiff might revive such tactics.

Advances in meteorology now predict strikes with 90% accuracy in some systems, potentially shifting blame from heavens to human oversight.

Could future suits target weather agencies instead? Or might they delve deeper into philosophical realms, probing the essence of responsibility in an unpredictable world?

The Penrose legacy lingers, inviting speculation on what happens when mortal courts summon the infinite.