One of Alcatraz’s last living inmates explains horrific details inside the prison as he addresses Trump’s plans to reopen it

Trump’s Bold Announcement Sparks Debate

On May 4, 2025, President Donald Trump announced a provocative plan to reopen Alcatraz, the infamous federal prison located on a rocky island in San Francisco Bay.

In a post on Truth Social, Trump declared, “REBUILD, AND OPEN ALCATRAZ!”

He argued that America has been “plagued by vicious, violent, and repeat Criminal Offenders” who belong in a rebuilt and enlarged Alcatraz.

The prison, closed since 1963 due to prohibitive costs, would serve as a symbol of “Law, Order, and JUSTICE,” Trump said.

Trump’s directive involves the Bureau of Prisons, Department of Justice, FBI, and Homeland Security.

He criticized “radicalized judges” and lenient policies, particularly toward undocumented immigrants, claiming the prison would house “serial Offenders who spread filth, bloodshed, and mayhem on our streets.”

Speaking to reporters, Trump called Alcatraz a “powerful” symbol but admitted it’s currently a “big hulk” that is “rusting and rotting”.

The announcement has ignited debate. Supporters see it as a bold move to restore law and order.

Critics, including experts and politicians, question its feasibility. Rep. Nancy Pelosi dismissed the proposal as “not a serious one,” noting Alcatraz’s status as a national park and tourist attraction.

The plan’s practicality remains uncertain, but it has brought Alcatraz back into the national spotlight.

Charlie Hopkins: A Window into Alcatraz’s Past

Charlie Hopkins, now 93 and living in Florida, is one of the last surviving former inmates of Alcatraz.

A Jacksonville native and former Golden Gloves boxer, Hopkins was sentenced to 17 years in 1952 for kidnapping and robbery.

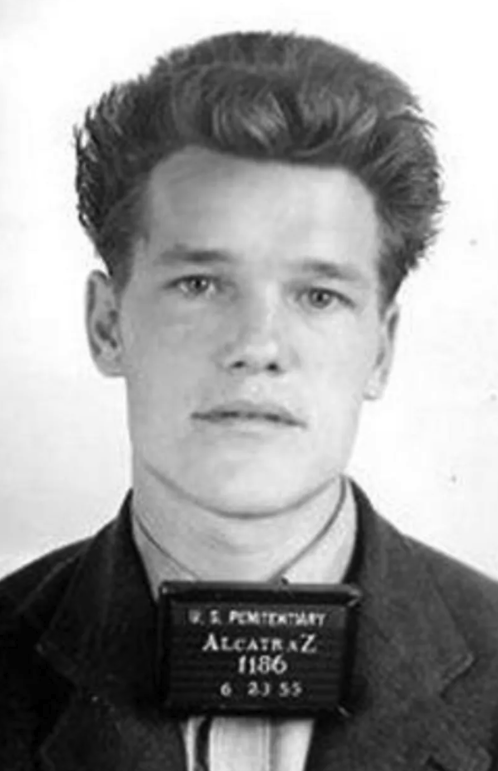

After causing trouble at other prisons, he was sent to Alcatraz in 1955, where he spent three years as Inmate #1186.

In a recent BBC interview, Hopkins shared haunting memories of his time on “The Rock”.

He described the prison’s “deathly quiet” as its most oppressive feature.

With no radio and few books, inmates faced relentless monotony. “There was nothing to do,” Hopkins said.

“You could walk back and forth in your cell or do push-ups.” The only sound breaking the silence was the occasional whistle of passing ships.

“That’s a lonely sound,” he recalled, likening it to Hank Williams’ song, “I’m so lonesome I could cry.”

Hopkins’ time at Alcatraz wasn’t without incident.

He befriended notorious inmates like Al Capone, Robert Stroud (the “Birdman of Alcatraz”), and James “Whitey” Bulger, with whom he later corresponded.

He also helped plan an escape attempt, stealing hacksaw blades from the prison’s electric shop to cut bars in the basement kitchen.

The plan failed, landing Hopkins in solitary confinement in “D Block” for six months.

After Alcatraz, Hopkins was transferred to a prison in Springfield, Missouri, in 1958. He was released in 1963, the same year Alcatraz closed.

He worked as a carpet fitter and hospital security guard, wrote a 1,000-page memoir titled Hard Time, and appeared in the TV series Alcatraz: The Last Survivor.

Today, he lives with his daughter and grandson in Florida, possibly the last living link to Alcatraz’s storied past, though another inmate, William Baker, was reportedly alive as of last year.

Life Inside Alcatraz: A Harsh Reality

Alcatraz was designed to be a “maximum-security, minimum-privilege” facility, housing the nation’s most incorrigible inmates.

Built in 1934, it held infamous criminals like Al Capone and George “Machine Gun” Kelly, but also inmates who were escape risks or disruptive elsewhere.

Prisoners had only four rights: food, clothing, shelter, and medical care.

Hopkins’ account paints a grim picture. The prison’s isolation was both physical and psychological.

Located 1.25 miles from San Francisco, it was surrounded by cold, treacherous waters, making escape nearly impossible.

The lack of stimulation was deliberate, meant to break inmates’ spirits. “It was the deathly quiet that got to you,” Hopkins said.

The silence, coupled with limited activities, created an environment of profound loneliness.

Despite the hardships, Hopkins found ways to cope. He formed bonds with fellow inmates, including gangsters and escape artists like Forrest Tucker.

His escape attempt, though unsuccessful, reflected the desperation of life on the island. “You had to do something to keep your mind busy,” he said.

Yet, the failed plan cost him dearly, with months in solitary confinement leaving lasting scars.

Feasibility of Reopening: Experts Weigh In

Trump’s plan to reopen Alcatraz faces significant obstacles. The prison was closed in 1963 because it was too expensive to operate.

Its remote location required all supplies, from food to fuel, to be transported by boat.

Maintenance costs were astronomical, with the salty sea air corroding the facility. By the time it closed, it was deemed unsustainable.

Today, Alcatraz is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, managed by the National Park Service.

It attracts over 1.4 million visitors annually, making it one of America’s most popular historical sites.

Experts are skeptical. David Ward, a sociology professor who studied Alcatraz, told TIME that the prison’s small capacity—around 300 inmates—limits its practicality.

Historian Ashley Rubin noted that Alcatraz was never the most punitive facility, serving more as a “public relations piece” than a true maximum-security solution.

The Reagan administration considered using Alcatraz for Cuban refugees in 1981 but rejected it due to its historical value and lack of facilities.

Political figures have also pushed back.

Rep. Nancy Pelosi emphasized the site’s tourism value, while others argue that the Justice Department’s budget, already facing cuts, cannot support such an expensive project.

Hopkins’ Take: Symbolism Over Substance

As a Trump supporter, Hopkins might be expected to endorse the plan. Instead, he’s skeptical.

“He don’t really want to open that place,” Hopkins told the BBC. “It would be so expensive.”

He believes Trump is using Alcatraz’s notorious reputation to make a point about crime and immigration.

“He’s trying to draw attention to the crime rate,” Hopkins said. “When I was on Alcatraz, a rat couldn’t survive. It’s not a place you’d want to be.”

Hopkins’ perspective is informed by his experience. He knows the prison’s harsh conditions and logistical challenges firsthand.

“Back then, the sewage system went into the ocean,” he noted, highlighting the need for costly upgrades.

For Hopkins, Trump’s proposal is less about reopening Alcatraz and more about sending a message: America must get tough on crime.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Trump’s Announcement | Announced May 4, 2025, on Truth Social; aims to house violent offenders. |

| Alcatraz History | Operated 1934–1963; closed due to high costs; now a national park. |

| Charlie Hopkins | Sent to Alcatraz in 1955; served 3 years; doubts Trump’s plan is serious. |

| Feasibility Concerns | High costs (billions), outdated infrastructure, current tourism role. |

| Expert Opinions | Historians call it impractical; limited capacity (300 inmates max). |

| Political Reactions | Rep. Nancy Pelosi calls it “not serious”; budget cuts complicate funding. |

A Symbol of Law and Order?

Trump’s call to reopen Alcatraz has reignited discussions about crime, justice, and America’s prison system.

Supporters see it as a bold statement, a return to a time when dangerous criminals were isolated from society.

Critics view it as a political stunt, impractical and out of touch with modern correctional needs.

For Charlie Hopkins, Alcatraz is more than a symbol—it’s a place of personal history.

His friendships with gangsters, his failed escape, and the crushing silence shaped his three years there.

Now, as one of the last living witnesses to Alcatraz’s past, he sees Trump’s plan as a rhetorical flourish rather than a feasible policy.

Whether Alcatraz will ever house inmates again remains uncertain. Its legacy as a fortress of punishment endures, but its future may lie in its role as a historical landmark, not a revived prison.

As the debate unfolds, Hopkins’ voice offers a rare glimpse into the reality of life on “The Rock”—and a reminder that symbols, however powerful, must contend with practical realities.